PRESIDENT TINUBU CONGRATULATES THE CHIEF OF THE AIR STAFF, AIR MARSHAL SUNDAY ANEKE, ON HIS BIRTHDAY

February 21, 2026

January 8, 2026 on Latest News, Press Releases, Speeches and Remarks

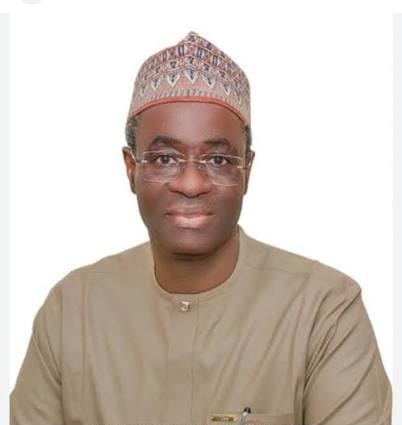

By Tanimu Yakubu

The Emmanuel Orjih’s essay being circulated is rhetorically powerful, but its “simplicity” is achieved by subtracting the very provisions that determine the outcome. That is not clarity; it is selective accounting.

The essay you circulated is rhetorically powerful, but its “simplicity” is achieved by subtracting the very provisions that determine the outcome. That is not clarity; it is selective accounting.

Let’s dismantle the argument on its own terms calmly, sequentially, and with arithmetic that actually follows the law.

1) The core confusion: pension and health insurance are not taxes—they are deductible contributions

A tax is a compulsory payment to government for general public purposes with no direct ownership claim by the payer.

A pension contribution is a deferred wage placed in a worker’s Retirement Savings Account—owned by the worker, regulated by law, and paid out to the worker later. Under Nigeria’s contributory pension framework, the employee contribution is commonly 8% (with an employer minimum contribution alongside it).

Likewise, national health insurance contributions/premiums are risk-pooling payments for defined health coverage, not a general revenue levy; and (crucially) they are among the items treated as deductions in personal income tax computations.

So when someone frames pension/health insurance as “proof the poor are being taxed,” they are committing a category error:

• A deduction is not a tax.

• A contribution you own (pension) is not a levy you lose.

• A premium that buys coverage is not a payment for “government enjoyment.”

If anything, the presence of these deductions is evidence of an attempt—however imperfect—to avoid taxing the portion of income being set aside for welfare/insurance.

2) The decisive arithmetic the essay avoids: the ₦800,000 tax-free threshold

Under the new regime described in multiple reputable summaries, the first ₦800,000 of annual income is taxed at 0%.

That is not a footnote. That is the hinge.

Now apply it to “Joseph”:

Monthly income: ₦75,000

• Annual income: ₦75,000 × 12 = ₦900,000

Under a system where the first ₦800,000 is taxed at 0%, Joseph is not “squarely inside” some punitive bracket. He is ₦100,000 above the zero band.

Even before deductions, the portion potentially exposed to tax is ₦100,000 per year.

If the next band is taxed at 15% (as these summaries indicate), then Joseph’s gross annual PIT exposure is:

• ₦100,000 × 15% = ₦15,000 per year

• ₦1,250 per month

Now add pension:

If Joseph contributes pension at 8% (even using the essay’s own assumption), that is:

• 8% × ₦900,000 = ₦72,000 in pension contributions annually (simplified)

That reduces the portion above ₦800,000 from ₦100,000 to ₦28,000. Tax becomes:

• ₦28,000 × 15% = ₦4,200 per year

• ₦350 per month

And if Joseph also has any deductible health insurance contribution (which many formal arrangements do), he can easily fall below ₦800,000 taxable income, making his PIT zero.

What this means

The essay’s “public U-turn” story is not proof that “the poor will pay tax.”

It is proof that the narrator’s demonstration did not apply the actual threshold structure that defines liability.

That is not logic. That is stage-managed arithmetic.

3) The poverty-line move: a PPP concept misused as a nominal naira salary cut-off.

The essay claims a World Bank “poverty line” of $4.20/day and then converts it into a naira monthly salary figure using a simple exchange conversion to get “₦190,000 per month.”

But the World Bank’s $4.20 line is reported in PPP terms (international dollars), not a naira-at-market-exchange salary threshold you can convert with casual FX math.

So the statement “everyone earning below ₦190,000/month is poor” is not an “irrefutable fact.” It is a conversion shortcut that swaps a technical welfare metric for a political talking point.

Even more: the World Bank updated global poverty lines in 2025 (with new PPP bases), which reinforces that these lines are statistical constructs, not the kind of direct nominal wage threshold the essay pretends they are.

4) “Widen the tax base” does not logically mean “tax the poor”

The essay’s claim is:

“The rich are already taxed, so widening must reach downward.”

That is a false syllogism.

“Widening the tax base” can mean (among other things):

• moving non-compliant high earners into compliance

• closing loopholes and leakages

• capturing parts of the digital and informal-but-affluent economy

• improving employer withholding integrity

• reducing avoidance via better administration

Nigeria’s revenue problem is not “the poor escaping.” Nigeria’s problem is a historically weak tax-to-GDP ratio and heavy reliance on borrowing; tax reforms have been publicly framed as part of reversing that.

So “widening” does not necessarily mean “drag subsistence wages into the net.” It often means: make the system catch who already should be paying.

5) The emotional overload: corruption lists are not an argument against the structure of a tax schedule

The essay spends pages listing possible misuses of public funds (A–Z). Some may be legitimate governance concerns, but they do not prove the specific claim being sold: “This tax takes money from the poor.”

If your target is accountability, the rational conclusion is not “therefore don’t tax.” The rational conclusion is:

• ring-fence, publish, and audit collections;

• improve transparency of allocation;

• tighten procurement;

• prosecute leakage;

• strengthen citizen oversight—using the legitimacy that taxation creates.

Historically, broad-based taxation has often strengthened demands for representation and accountability (“no taxation without representation” is not a slogan of lending institutions; it is a logic of citizen-state bargaining). The essay flips that logic on its head by implying that lenders fear Nigerians paying taxes because taxes would empower citizens. That is not an argument; it is a narrative device.

Meanwhile, Nigeria’s borrowing constraints are real, and a reform agenda that reduces debt-dependence is not “indifference”; it is sovereignty through solvency.

Proof-by-proof: what the essay is doing (and why it misleads)

Deception 1: Re-labelling deductions as “taxes”

• Pension/health insurance are framed as “proof of taxation.”

• In reality, they are welfare-linked contributions and deductions that reduce taxable income.

Deception 2: Ignoring the 0% band

• The ₦800,000 annual tax-free threshold is the central fact.

• Without it, the story can manufacture outrage at ₦75,000/month.

Deception 3: PPP poverty line converted as if it were a salary threshold

• $4.20/day is PPP-based and not meant for naïve FX-to-naira monthly wage claims.

Deception 4: False dilemma

• “Only three possibilities: the poor, livestock, or ghosts.”

• Serious tax administration realities are ignored to force a punchline.

Deception 5: Moral indictment substituted for computation

• A–Z allegations create heat, not proof.

• Even if every allegation were true, it still wouldn’t change the tax schedule math.

The bottom line

If you want to disagree “most vehemently and logically,” this is the clean core:

1. The new structure explicitly shields low incomes via a large zero-rated band.

2. Pension and health insurance deductions are welfare design features, not stealth taxation.

3. The essay’s outrage depends on omitting the very thresholds and concepts (PPP) that make its conclusion collapse.

Yakubu is the Director-General, Budget Office of the Federation

Nigeria,